“I never fired

a shot in anger,

I’m pretty proud

of that.”

— Jim Spiers, 97

Jim Spiers

In Profile pays tribute to the ultimate good keen man

It is with sadness we record the death of Jim Spiers, the second person to feature when the series launched last year.

He died on August 10, five weeks and two days after celebrating his 99th birthday.

The long and fulfilling life of John James Kennedy Spiers (to honour him with his full name) was celebrated at his final farewell on August 16.

There was standing room only for those who came to salute this career forester who began his working life as a South Island tree feller and ended as the founding boss man of the Logging Industry Research Association (LIRA) based on Rotorua’s FRI campus.

He went on to become an avid traveller, covering the world from the South Pole to its Northern equivalent as he indulged his love of skiing across the globe. In addition, he was an avid tramper, fisherman and hunter.

But it was his war years In Profile highlighted.

It is generally believed he held this country’s record for serving in the most armed services during the Second World War.

His military service began when he enlisted into the army in Invercargill during 1941.

He went on to wear the uniforms of the New Zealand Air Force (before it became the RNZAF), the Royal New Zealand Navy, the Royal Navy, and the American Navy before fulfilling his ultimate aim of securing the wings of a Fleet Air Arm pilot.

Despite such a varied fighting force line up Jim was proud that he never fired a shot in anger.

We thank him for allowing us to record the story of his action-packed life.

Farewell Jim. You were the ultimate good keen man.

Jim was interred at the Rotorua RSA cemetery. He is survived by two sons and two daughters.

- Jill Nicholas and Stephen Parker

The low-key war vet whose service embraced multiple fighting forces

Now here’s a brain teaser to do battle with.

How can it be that Jim Spiers, a fourth generation Kiwi, spent his four years of Second World War service wearing the uniforms of five fighting forces?

The solution: Like many young men Jim’s ambition was to win his pilot’s wings via the British Fleet Air Arm. That was fine with the military brass but in the strange ways of war they sent him leapfrogging from one armed service to another before he achieved his goal.

Each time he entered a different service his wardrobe changed.

First up he wore the khaki of his homeland’s army, followed by the garb of its navy and air force.

That was before moving on to Britain’s Royal Navy, home of the Fleet Air Arm, followed by the American navy. This is where Jim’s wings became a reality and led to a war record that reads like a travel log lifted from the pages of a Boys Own adventure yarn.

His US link is appropriate for someone who describes himself as a ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’. “I was born on July 4, American Independence Day,” he chortles.

His almost 98 years may have dimmed his sight, he carries a white stick, but his wit remains rapier sharp and there’s a glint in those impaired eyes of his as he escorts the In Profile team through his life.

And what a life it’s been.

His war service apart, the former senior forester has travelled from the Antarctic to the Arctic with so many countries in between his piles of passports have hit stamp overload.

Then there’s his post-war skiing both on and off piste. If there’s any ski field in New Zealand he hasn’t skied on it’s not worthy of mention.

His North American tally’s “probably” in the 40s with at least 26 throughout Europe plus an uncounted assortment of “elsewheres”.

It’s ironic that despite growing up within sight of the Southern Alps Jim didn’t learn to ski until his post war years and it wasn’t in the land of his birth but in Oz where he was studying for a forestry degree.

Wartime conscription

But all that’s way distant from his war time memories which began when he was enlisted for military service in Invercargill during 1941.

His induction into military life was as a foot soldier.

“They bloody well route marched me through Southland, okay so that was a bit of an exaggeration but there were a hell of a lot of route marches and drills.”

It was a good way to break in his boots for his transfer to Burnham Military Camp. It coincided with a particularly cold winter.

“There were a hell of a lot of route marches out in the Waimakariri River area, we didn’t always have tents. It was good if you could get shelter under buses or trucks, ha ha to that.”

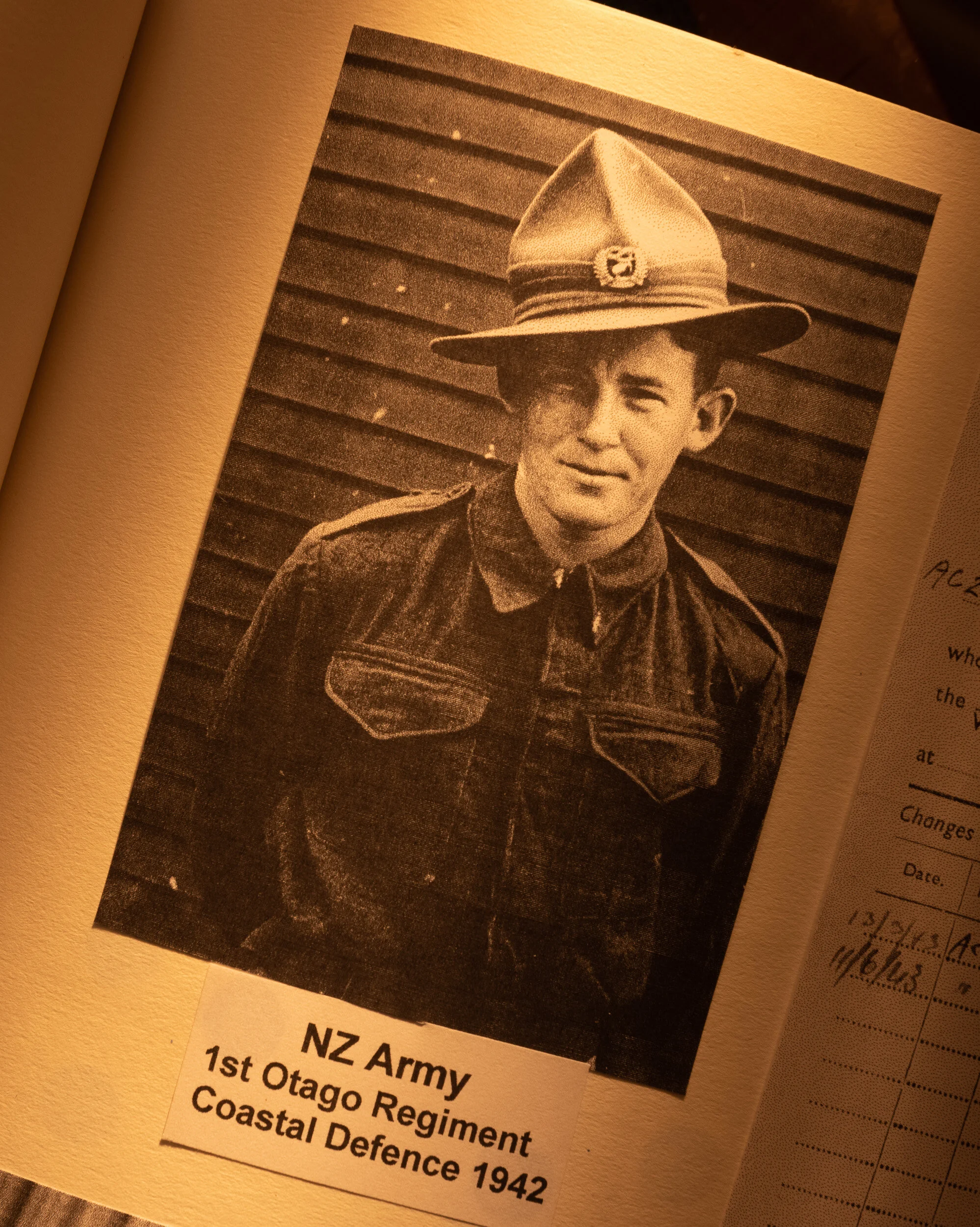

Assigned to the Third Otago Regiment Jim and his platoon mates were sent to defend the Otago coast.

“We only had World War One .303rifles and an ancient Lewis machine gun, thank God the Japs never came.”

A man easily bored, Jim gave up on the army. “I wanted something more exciting, a friend told me about the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm, I had to apply to the navy to get into it but somehow found myself in the air force.

“I had my first ride in an air force plane at Milson near Palmerston North. I reckon they were checking whether your stomach could stand flying.”

Jim’s could but he was returned to the navy. “My guess is they wanted to keep their men alive.”

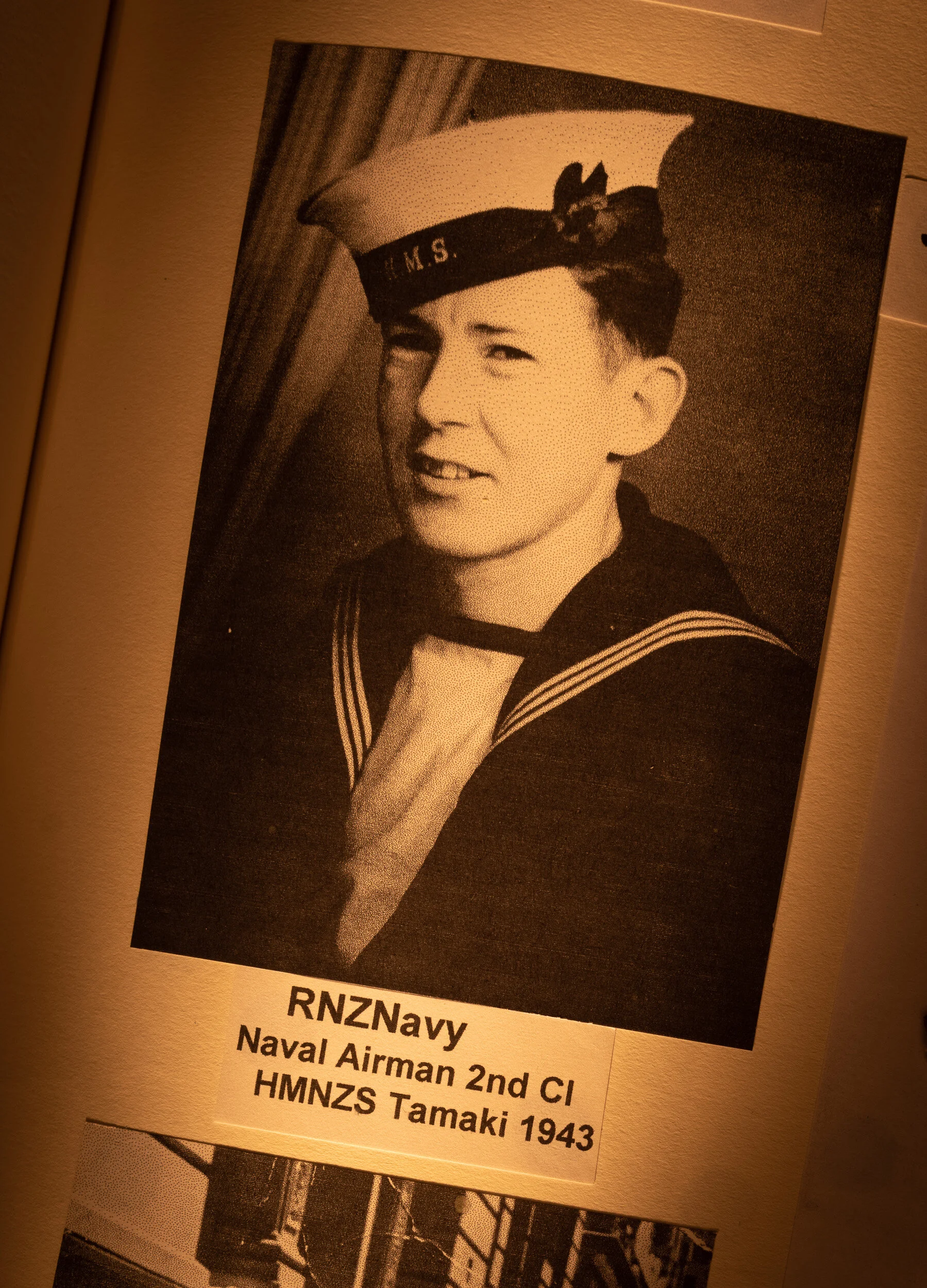

His first posting was to the naval training establishment HMNZS Tamaki, and then based on Motuihe Island in the Hauraki Gulf. There he was in for three weeks “non-stop, hard out” drill before being directed to Wellington, his future destination highly classified.

Overseas adventures

“From Wellington we sailed on the Dutch liner Nieuw Amsterdam, There were all sorts of people on that trip across the Pacific, Aussies, Brits, South Africans and a lot of German and Hungarian prisoners from the North Africa campaign being taken to the US, they were kept below decks well away from us.”

The general consensus on board was they were heading for the Panama Canal.

“Then once we gathered we were too far north to be going through it we started betting on where we might go, LA, Seattle, Vancouver and various other places, but then one morning we were coming straight towards a large, long white cloud with two mighty red pylons sticking out.”

It was the Golden Gate Bridge.

“When we burst out of the cloud and sailed under it there was this beautiful white city with the sun shining on it, it was San Francisco. I’ve been in love with San Francisco ever since.”

After four days shore leave the Kiwi contingent boarded a train heading east. “We stopped in Chicago where we were shunted into the abattoirs.”

In New York Jim was as fascinated by its towering skyline as he had been by San Francisco. “It was another sight for a Kiwi boy to behold.”

“In New York we were quartered in the Brooklyn Navy Yard with plenty of time to look around and attend social events. At one I met a very nice girl, her name was Muriel Duffy, my first overseas girlfriend. I kept in contact with her for quite a few years.”

Leave over, the Kiwis boarded the liner that would take then across the Atlantic, it was the Queen Mary with the Kiwis sardine canned into what, in peace time, had been a first class cabin.

“On that trip it had 17000 on board. Some people tell me that’s an exaggeration but I don’t think it is, they were all jammed into all sorts of corners. We had a two berth cabin with 24 in it, it had been stripped to the bone and bunks inserted up the walls.”

After ziz-zagging across the Atlantic dodging German subs they docked in Grennock on Scotland’s Firth of Clyde, an area close to the home of Jim’s forefathers.

Another train trip took him through Britain to the Fleet Air Arm’s training base at St Vincent in Gosport.

At St Vincent they only did very basic naval and air training but no flying. They did not want raw students shot down by the occasional intruding German aircraft . So next it was back across the Atlantic on the Queen Elizabeth to New York City and then by rail into Canada.

“I did see Muriel again there.” There’s another of those cheeky guffaws he’s so good at. Their reunion was fleeting.

“We were split into two groups for flying training, one went to New Brunswick, the lot I was in headed to the US navy flying base in St Louis, Missouri. That was the first place we had any actual training in flying.”

Jim’s initial tuition was in a Stearman bi-plane. “We called it the Yellow Peril, a replica came to Rotorua in 1988.” Naturally Jim went up in it. “Just as a tourist for old time’s sake.”

Jim assigns his St Louis training to the very tough category.

“More than half the course failed yeah, me too. I only got 88 hours up. It was the biggest disappointment of my life.””

Jim remained determined to fly so it was back to Britain, but not for long. His war time yo-yoing to eventually see action returned him to the States, this destination a US navy port in Norfolk, Virginia.

Closely examining the giant photograph album that chronicles his war years Jim confirms his memory of so much sea and land time is in correct order.

“I can tell where I am by the girls . . .”

There’s a story behind those photo albums. The first few pages carry pictures shot covertly by his best mate, Russ Spiller, a Napier professional photographer. “It was against the rules for servicemen to carry cameras but somehow Russ had hung on to his then somewhere along the way I managed to acquire my own.”

Thank goodness he did. It’s a record of where he was when that’s probably more accurate than any written documentation would likely be.

From Virginia he boarded an American freighter bound for the British West Indies.

“We sailed down its chain of islands via Havana and Guantanamo Bay before berthing in Trinidad.”

Why Trinidad? “You may well ask. At that time England was getting a lot of its supplies from South America, this meant we were having very good training because a lot of those supply ships were being sunk by German subs.

“I flew a variety of aircraft as an observer-navigator and finally got my wings there [Trinidad] and was promoted to sub lieutenant.”

By the time Jim earned the wings he’d coveted for so long the war was almost over, he was in Trinidad when it ended. The celebrations are seared into his memory.

“The people of Trinidad were of all colours, the music was great, the noise almost as bad as wartime so there were a wild few days there at the war’s end.”

Forestry career

It wasn’t until well into 1946 that Jim returned to Aotearoa.

Like many servicemen reacclimatising to Civvy Street he “fluttered around a bit” before returning to Southland where he’d previously worked in the bush.

“I went into the [forestry] conservator’s office and told him I’d returned from the war and wanted my job back. He dragged out my file, looked through it and said ‘good God boy, we’ve now got to pay you a high sum of money so you’d better get out there and earn it.”

Jim earned his by timber cruising, that’s measuring blocks of trees for sawmills.

However he soon came to rue the lack of social life in the wops, especially being deprived of female company.

“I applied though the Forest Service to go to Otago University they didn’t think I was suitable so I got in through the military and studied for a science degree.”

His first long varsity vacation was spent in Rotorua working with a Waipa logging gang.

“It was manned by Maori guys from Awahou who treated me and another trainee very well, at Christmas they got a bonus, when we didn’t they chipped in and came up with a bit of money for us. Since then I’ve always thought particularly well of the generosity of Maori, especially Awahou Maori.”

To do justice to the rest of Jim Spiers’ forestry years would require a book in its own right. Jim has written one, it’s entitled When Forestry Was Fun.

Don’t bother asking him if it no longer is, he clams up, something out of character for a man who, until this juncture, has spoken so volubly about his life and times.

To parcel up Jim’s forestry years: his was a post war job that took him to universities in Canberra to acquire a forestry degree and British Columba to gain one in forestry engineering.

He’s worked in virtually all the North and South Islands forestry hot spots. Locally these embraced Minginui, the Ureweras and Kawerau serving there twice, the second time as office in charge of Kaingaroa Forest for nine years.

He was in Minginui when he met his wife-to-be Pauline Eccles, a physio working in Rotorua.

“We met at a dance, I met all my girlfriends at dances.”

His forestry career closed in 1984, almost a decade earlier he’d set up the Logging Industry Research Association, (LIRA) based in the FRI’s (now Scion) grounds.

“If you want to know about the rest of my life since retiring it’s is over there.” “Over there” is a towering bookcase packed with photo albums recording his extensive travels and ski field exploits.

When Jim became testy about where the fun went out of forestry a tactical retreat to less contentious territory was called for.

That returns us to ‘Jim’s war’ and how he views the unusual role he played in it.

First up he’s emphatic it’s noted that he wasn’t idly sitting around the various bases he was at while waiting to be moved to yet another training ground.

“This is where school room training came in, having practical sessions with the equipment we were going to use. I think we got far more education on the theory of war than a lot of the other forces did.”

He’s also anxious to clarify any confusion about how he came to wear other countries’ uniforms. “When we were with the Royal Navy and Fleet Air Arm we wore their uniforms, in the US Navy we wore theirs but all the time we were still with the New Zealand Navy.”

And let the record state Jim has no illusions about being anyone special simply because his service was out of step with the military’s main stream.

“I don’t think too many generals and leaders would be too pleased that I did so many things, went to so many places but didn’t take much part in the action.

“Sure, I wore all those uniforms and fired plenty of practice shots but I never fired a shot in anger, I’m pretty proud of that.”

JIM SPIERS – THE FACTS OF HIS LIFE:

-

Born

Dunedin, 1923

-

Education

St Patrick’s primary and St Kevin’s secondary schools, Oamaru. Final half year with Christian Brothers Dunedin. Universities in Otago, Canberra, British Columbia

-

Family

Two sons, two daughters. “No grandchildren, that’s very unusual.”

-

Interests

Family, friends, photography, skiing, travel, keeping fit . “Now I’m sight impaired I can’t do much but try to go into town on the bus two or three times a week. On one of those days I walk through the Government Gardens, another through town. I generally end up having a cup of coffee at Café de Paris. I use a walker on all my trips. The traffic is very courteous to me and the bus drivers very helpful.”

-

On his Life

“I have had a very good life with too many highlights to mention.”

-

Personal philosophy

“I’m not a philosopher.”

*Footnote: Whether Jim’s service to so many fighting forces is a record is a matter of conjecture, it may have been equalled but no hard evidence has been found to substantiate that. If there are others whose service was as diverse as Jim’s he, In Profile and the RSA would welcome learning of it.